GE’s Alstom acquisition: the case of purchase price accounting gone wild

Last week, the Wall Street Journal published an article titled "How GE Built Up and Wrote Down $22 Billion in Assets". The piece describes a somewhat puzzling scenario: when GE purchased Alstom SA's power business in November 2015, it paid approximately $10.1 billion for the assets acquired. But by the time GE finalized its purchase price allocation and acquisition accounting for the deal a year later, the amount of goodwill that was recognized in GE's business combination accounting exercise was $17.3 billion.

I have never owned shares of General Electric Co. (GE) — and that's a good thing, given what the stock's five-year chart looks like — but given GE's recent financial woes, I was intrigued enough by the WSJ's piece that I decided to geek out, put my equity research analyst hat back on, and see if there were any clues investors could have reverse-engineered from this business combination accounting that the Journal described as "unusual". (At least unusual enough for the Department of Justice to be looking into it.)

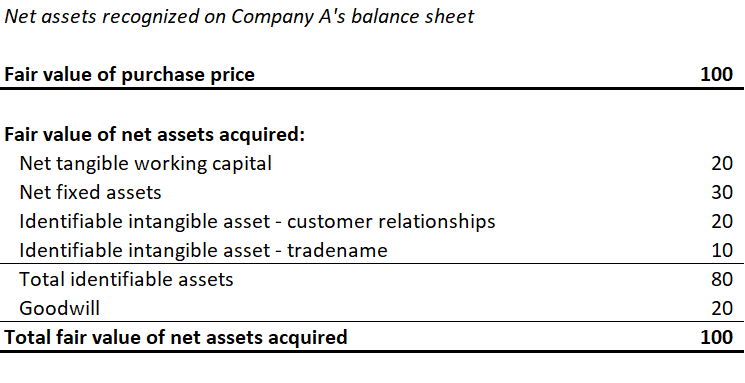

Purchase price accounting 101

Suppose Company A buys Company B for $100. Under both IFRS and US GAAP, accounting rules would require Company A (the acquirer) to recognize the fair value of the net tangible assets and identifiable intangible assets that were acquired as part of the transaction. Anything that is deemed to be 'unidentifiable' ends up classified as "goodwill" on the balance sheet. In this highly simplistic example, the 'purchase price equation' might look something like below:

The evolution of the purchase price allocation for GE's acquisition of Alstom's power business

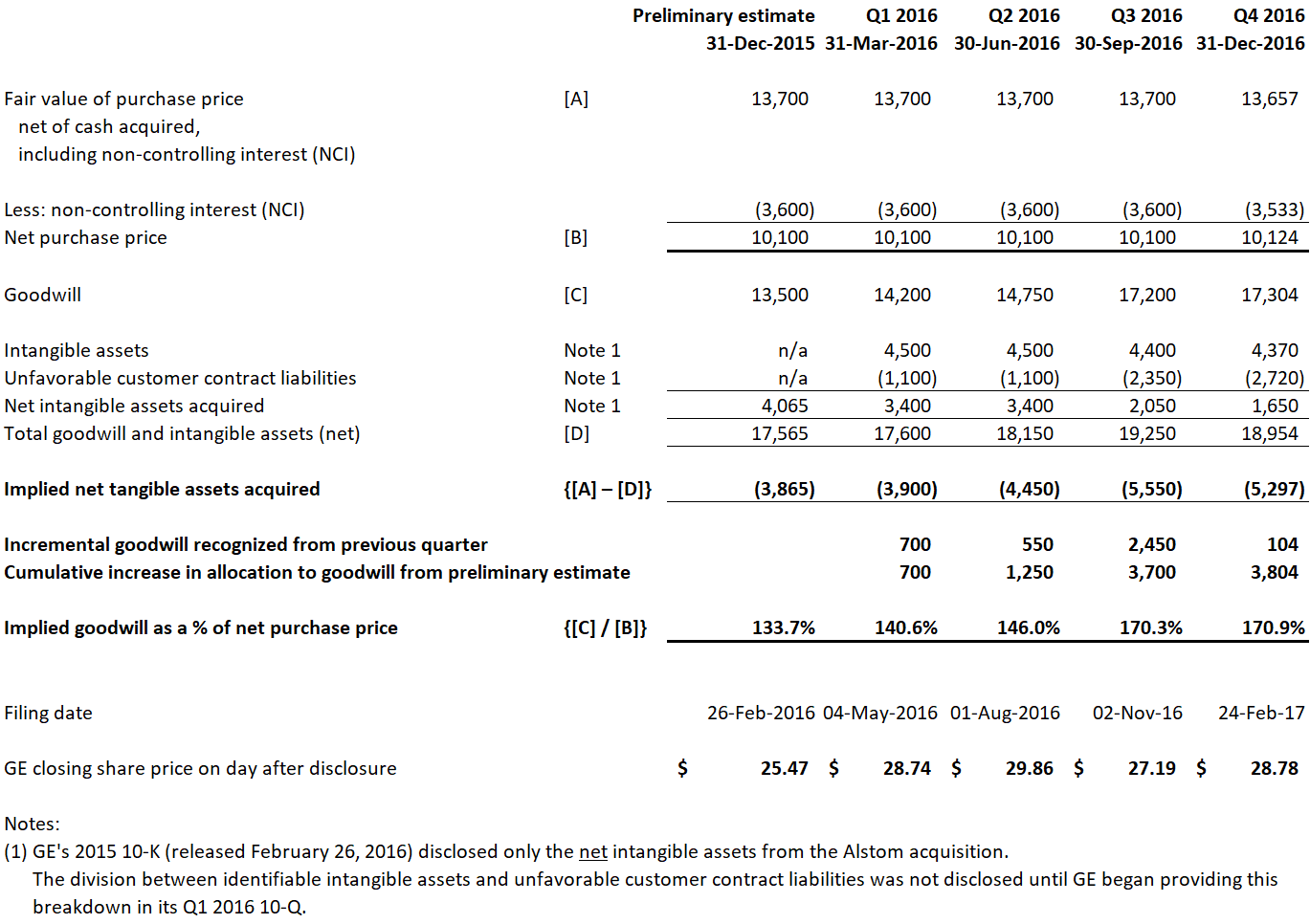

GE's acquisition of the Alstom power business closed on November 2, 2015. At the time, GE disclosed an initial fair value of the purchase of $10.1 billion (net of cash acquired and net of a non-controlling interest (NCI) of $3.6 billion).

Under accounting rules, acquirers typically have a year to finalize their estimates of the fair values of net assets acquired in a business combination. And with this acquisition, GE took its sweet time, updating its fair value estimates every quarter from Q4 2015 to Q4 2016.

As shown in the table below, the "allocation" of the purchase price between goodwill and other assets gradually changed every quarter following the acquisition:

What is the noticeable trend here? In every quarter, GE revised its estimates to allocate more of the total purchase price to goodwill and less to other identifiable assets (both tangible and intangible). Initially, in Q4 2016, GE estimated the fair value of goodwill acquired at $13.5 billion. A year later, when the purchase price allocation was finalized, the goodwill figure had risen to $17.3 billion ... or approximately 70.9% more than the fair value of the $10.1 billion net purchase price.

How GE rationalized the recognition of its goodwill

GE's November 2, 2015 press release indicated that the Alstom deal would result in EPS accretion of $0.05 to $0.08 (by 2016) and $0.15 to $0.20 (by 2018). Given that GE had a ballpark share count of about 10 billion shares outstanding at this point in time, this would have translated into near-term earnings accretion of approximately $5 billion to $8 billion by 2016, increasing to $15 billion to $20 billion by 2018.

Every transaction has a story, and the investment thesis behind the GE-Alstom acquisition was to realize synergies — a lot of synergies. Embedded within GE's estimate of earnings accretion were targeted cost synergies of $3.0 billion by the fifth year following the acquisition.

Why is this important? When it comes to synergies, under fair value accounting rules, the million-dollar question (or in this case, $17 billion question) becomes whether transaction synergies are buyer-specific (i.e., available only to GE) or "market participant" synergies (i.e., synergies that could be attainable by any acquirer in a likely pool of buyers).

In its 2016 10-K, GE stated that, "The amount of goodwill recognized compared with identifiable intangible assets is affected by estimated GE-specific synergies, which are not permitted to be included in the measurement of identifiable intangibles. Such synergies include additional revenue from cross-selling complementary product lines." In other words, in pricing the Alstom transaction, the magnitude of the synergies that GE was banking on achieving was so significant that they resulted in the initial goodwill recognized on the balance sheet being greater than the purchase price itself. Said differently, GE's purchase price allocation implied that the company was paying $10.1 billion for a business with a negative fair value of net identifiable assets.

As the table depicts above, with every passing quarter, GE revised its estimates for the Alstom deal to allocate more of the purchase price to goodwill and less to separately identifiable intangible assets. While this may not necessarily be overly alarming on its own, it likely reflected the reality that, in order to justify the purchase price paid and the resulting goodwill, GE would need to achieve a high bar in realizing the anticipated GE-specific synergies in the years following.

The shifting of value from 'identifiable' assets to goodwill also means that the nature of the future economic benefits from the GE-specific synergies were inherently riskier than 'market participant' synergies that could be attributed to identifiable intangible assets.

Did investors care?

As the purchase price allocation for Alstom was tweaked and tweaked again, GE's share price remained in a fairly tight trading range, as shown by the closing prices at each quarterly filing in the table above. This begs the question: did investors care about the purchase price allocation exercise?

It's a difficult question to answer, given GE's complexity as a conglomerate operating in different industries. After all, GE reported approximately $70.4 billion in total goodwill on its balance sheet (across all segments) at the end of 2016 and almost $84 billion at the end of 2017. Would the allocation of an additional ~$3.8 billion of goodwill from the Alstom transaction (the difference between GE's initial estimate in Q4 2015 and the finalization of its purchase price accounting in Q4 2016) really catch an investor's eye as being noteworthy?

What caused GE's stock price to tank

In looking at the five-year price chart for GE's stock, there were 12 days during the period from April 2014 through March 15, 2019 where GE's share price decreased by more than 5% in one day. Of these days, six were most the notable:

- November 13 and 14, 2017: shares fell following GE's announcement that it would cut its quarterly dividend by 50% (from $0.24 per share quarterly to $0.12 per share);

- May 23, 2018: shares fell following GE's guidance that there would be no profit growthduring the year for its power business;

- October 30, 2018: shares fell following GE's third quarter earnings release, in which the company impaired virtually all of the goodwill from its power segment and indicated the company would be all but eliminating its quarterly dividend (from $0.12 per share to $0.01 per share) and indicated that the SEC was widening its probe of the company's accounting practices;

- December 4, 2018: shares fell again in advance of the day on which GE made its dividend cut -- to one penny per share -- official; and

- March 6, 2019: shares fell following more negative guidance from the company for the remainder of 2019. (The company conceded that it would not generate any positive operating cash flow during 2019.)

What about impairment testing?

As any good accounting nerd would know, goodwill is subject to impairment testing at least annually under GAAP. Interestingly, GE performs its impairment testing each year during its third quarter using information known as of July 1.

In its Q3 2017 goodwill impairment note, GE impaired approximately $1.2 of the $26.4 billion of goodwill in its power segment. The stock price had already been dropping leading into Q3 2017 earnings, and while the actual release of Q3 2017 earnings didn't stop the bleeding completely, it didn't cause the share price to completely bleed out, either.

It was in Q3 2018 that GE decided to impair the vast majority of the goodwill in its power segment ($21.1 billion of $25.3 billion). This earnings release came on October 30, 2018, on which GE's share price fell by almost 9%. However, in my view, the more important catalyst for the stock that day was not the impairment charge; rather, it was the near wipe-out of GE's dividend (and, possibly, the cringe-worthy headline that the SEC and DOJ would be further scrutinizing its accounting practices).

By the time GE decided to impair the goodwill in its power division, the stock was trading at around $10 -- well below the $28.78 at the time of the finalization of the Alstom deal. Much of the impact from the 2017 dividend cut and the May 2018 guidance with respect to the power segment had already been priced in. (Given that GE was already bearish on its power division by May 2018, it raises the question of whether an impairment charge ought to have been booked in Q2 2018.) But the second dividend cut — or can we call it an elimination? — was presumably what caused the trough in GE's stock price in late 2018. (There is an old saying in stock analysis that "a dividend cut is never fully priced in".)

The bottom line

Accounting standard setters across the globe have attempted to implement rules and principles to make financial statements more informative for users through the complex accounting and disclosure requirements prescribed with respect to both business combination accounting and subsequent requirements for impairment testing. We certainly need accounting rules and principles in place, and when it comes to purchase price accounting and valuation for financial reporting purposes, helping clients follow these rules is a critical piece of my own professional practice as a business valuation specialist.

That said, from my personal — albeit short — experience as a sell-side equity research analyst, I am of the view that investors aren't necessarily primarily focused on analyzing trends in business combination footnotes.

In the case of GE, the recognition — and subsequent impairment of — a material chunk of goodwill certainly didn't help the cause for GE's falling share price. But it isn't apparent that the disclosures required under business combination accounting were meaningfully influential on how financial statement users valued the shares of GE at the time the disclosures were made. Rather, my interpretation of the data is that GE's stock was slaughtered more on the news of two dividend cuts and successive iterations of weak earnings guidance than by an egregious impairment charge.

On a positive note, this is evidence that markets are at least somewhat efficient in responding to new information and management signalling through dividend policy.

However, a more interesting takeaway for professional accountants in this case is a reminder of the importance of timeliness as a fundamental characteristic of accounting information.

Clearly, GE investors were well ahead of the accountants in pricing in the effects of future decreases in cash flow from the company's power division. (Perhaps that is why GE's board is "opening the door" on replacing KPMG as its auditors after 109 years of service.) GE's goodwill impairment charge in Q3 2018 was significant, but as significant as it was, it may have been old news to investors — which highlights the need for timeliness if GAAP financial statements are supposed to be useful for users.

Given the flurry of unfortunate headlines for GE, the question of how much weight investors placed on the Q3 2018 goodwill impairment charge (as opposed to other pieces of bad news) remains up for debate.

Now that the SEC and the Department of Justice are looking into the matter, we can wait and see what they have to say about it.